Four years ago, the siege of Marawi placed the barbarism of the Islamic State squarely in the backyard of the United States. As the engagement opened up, Marawi soon turned into the “Fallujah” of the Philippines.

Having long since been extinguished, the “Marawi Problem” appears to have potential for resurgence, and may possibly serve as a text book example of how all phases of counterinsurgency must be addressed in order to be considered a successful campaign.

Hearts and Minds

In every insurgency, both the state and the insurgents acknowledge the strategic value affixed to the “Hearts and Minds” of an affected population. As such, a substantial consideration must be applied to the population as a center of gravity when conducting counterinsurgency operations.

The U.S. Army Field Manual – FM 3-24 Counterinsurgency divides the population into three distinct groups, “An Active Minority For the Cause, An Active Minority Against the Cause, and a Neutral or Passive Majority.” A basic course in statistics will demonstrate that the Passive Majority registers as the critical demographic that can mean the difference between success and failure.

While an appropriate poll has never been taken of the citizens of Marawi, it appears that ISIS and its supporters represented a very small minority during the siege. That said, it would be safe to say that a vast majority of Marawi’s citizens rejected the idea of the “new caliphate” despite its vast population of Practicing Muslims.

In hindsight, it appears that this was a strategic oversight on the behalf of the ISIS militants that ultimately resulted in their demise, both tactically and politically. That said, it appears the Islamists are now demonstrating a very clear understanding of the basic dynamics of insurgency.

On May 21, 2021, Benar News reported that a total of 17,000 families remain displaced as a result of hostilities in Marawi. These are likely those who fled the city during the offensive, certainly not representative of the minority in support of the siege. Debriefing of surrendered militants revealed that ISIS is actively recruiting in the rural and impoverished areas surrounding Marawi, likely the terminal for the diaspora of Marawi “refugees.”

The surrendered militants also utilize the government’s “broken promises” to rebuild the city as a fulcrum for an effective recruiting campaign. This success is catalyzed by the ever present sentiment of Muslims that the Government is indifferent to their plight. It is very easy to insinuate that the government’s slow response to rebuilding is due in part to differences between the Muslims and the Catholic Majority of the Philippine population.

Whether true or not, the aforementioned narrative is not hard for a reasonable, disenfranchised, and impoverished person to believe. As such, ISIS appears to be taking a significant interest in this opportunity and is actively capitalizing on it.

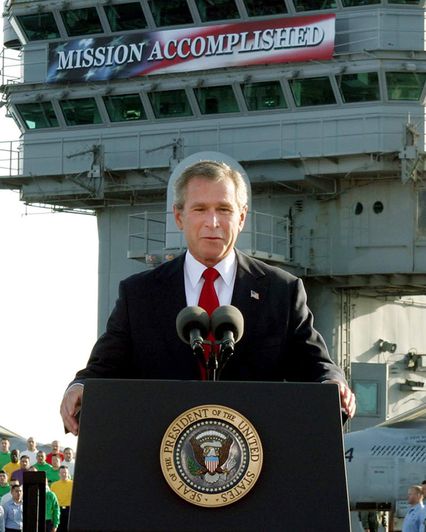

A fundamental strategic mistake that tacticians make in light of a tactical counterinsurgency victory, is declaring victory prematurely. Arguably, such is human nature to view conflict in terms of attrition and tactical defeat.

Mission Accomplished?

The United States made this highly publicized declaration mere hours after the fall of Baghdad. As we all know, the fall of Baghdad was only the beginning of a painfully long conflict that claimed countless civilian and military lives. In the end, neither belligerent could reasonably claim victory, with the civilian population holding the highest price paid during the conflict.

Military leaders should consider the tactical victory as the official start of the counterinsurgency campaign. As well read strategists will contend, an effective counterinsurgency is fought with bags of rice, not bullets.

The reality is that open, conventional warfare, while the “last” phase of insurgency, morphs back into phase one or the “insipient” stage, upon its conclusion. This is demonstrative of the cyclic nature of insurgency sans the linear nature of conventional warfare. In “war,” belligerents will claim victory or declare surrender, often brokered into a formal cessation of hostilities. However, this is not the nature of insurgency as is demonstrated time and time again.

Further, in conventional warfare, the adversary consists of combatants, whereas the true enemy is simply an idea. These ideas, weather pro or anti-government live within the collective consciousness of the civilian population. While combatants on both sides are sound in the ideals of their given side, it is the population who can tip the scales towards victory by either side, bringing the losing faction to its knees, begging for a compromise.

It is the goal of the government not to find itself in such a predicament. An effective campaign at this stage of insurgency requires a lot of money and a lot of sustained engagement with the civilian population. In absence of a government led effort, it is the insurgents who fill that void with promises of their own. The only leverage ISIS has at this point is that they have yet been afforded the opportunity to break any promises.

As with any complex insurgencies, the state sustains a substantial loss in blood and treasure in re-establishing order and security in the region. However, counterinsurgency is a topic very heavily examined since the American Revolution.

As such, the wealth of literature and research in the topic presents a very substantial case for ensuring the proper and thorough execution of COIN operations. Failure to do so will turn a short term success into a long term failure as learned by U.S. strategists in what amounts to nothing short of a series of failures of which, the consequences manifested decades after the conclusion of the engagement. It appears Marawi runs the risk of becoming the most current vignette in the counterinsurgency manual.